Our Principal Investigator, Dr. Meaghan Peuramaki-Brown, wrote this week’s blog post. Although this starts out as a “me, me, me” piece, please hold on until the end, where you’ll see it is very much not!

I had no idea what to write about this week—I like to assign blog posts for others to write but regularly dread writing my own. I could have talked about what we’ve been finding this season, but I’ll leave that for next week, our final week of excavations. So, I thought I’d write about what it is I do as the Principal Investigator (PI) of the Stann Creek Regional Archaeology Project (SCRAP)—well, at least some of what I do.

Belize’s Institute of Archaeology (IA) requires one individual to take on the PI role of a research project/ program, even though we have multiple co-directors on SCRAP. The PI is the individual responsible for preparing, conducting, and administering a research project. In Belize, the PI must have a Ph.D. in Archaeology or Anthropology and have a minimum of 5 years of experience working in the Maya or Caribbean region. Additionally, they must have “employment and be in good standing with an accredited academic institution.”

However, hanging everything on one person is dangerous. What if something were to happen to me? That is why we also have an Associate Investigator—typically, Dr. Shawn Morton is ours for SCRAP. This individual is as familiar with all the project’s inner workings and can step in for the PI if necessary. For those who follow our Old Bezanson Archaeology Project (@obaparky on social media), Shawn is our PI there, while I serve as the Associate Investigator–as a result, we take turns sharing the load for our two projects! Reminds me of the old Sesame Street song, “Cooperation, makes it happen! Cooperation, working together!”

My primary role as PI is charting our project’s overarching research direction and design, with input from our co-directors (Dr. Shawn and Dr. Jill Jordan) and, whenever possible, local community members. This includes integrating others’ research desires and plans, such as those of graduate students. I’m also responsible for applying for our annual permits and the grants that fund our research. We’re currently finishing up a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Insight Grant. We will apply for a future SSHRC Partnership Development grant to expand our Alabama research to other parts of the Stann Creek District and formally incorporate Belizean-Maya organizations as partners in the research. But more on that another time. Most of this work happens before we arrive at the field site, though the local consultation I engage with happens year-round.

If it seems as though I’m not in many of the field photos you see on social media, it’s because I’m often behind the camera, helping to document the day-to-day of our research (#scraparky #realarchaeology) and busy taking general notes. In the field, I also ensure everyone stays on task, provide ongoing advice on best approaches, and warn them when some strategies seem destined to fail (e.g., “That tarp set-up will not protect you or your unit from rain”). I always want to supervise my own excavations and relive the joy and relatively “simpler” times of my archaeological career, but I rarely get the opportunity to do so. This often causes me to live vicariously through (and annoy) excavation supervisors who get to be in the thick of the “real archaeology” each day. To be honest, I’m often a pain in the ass, after which I feel like a hag who should quickly retreat to the hovel from whence she came.

Over the years, as we have become a more established presence in the district, we’ve acquired more and more responsibilities as well as connections, networks, and communities that now seek us out for any number of reasons—these elements are what occupy most of my time while in Belize. Often, I have to leave the field site to deal with any number of tasks. I fetch a lot of stuff for the rest of the crew so they can do their jobs properly. I also prepare and implement our health and safety plans, organize food and accommodations, manage our finances, handle pay/social security, and plan and conduct outreach activities (including social media elements) with various advisers and representatives. I liaise with the IA on a number of matters, which at times requires me to travel to Belmopan. I’m also serving as interim lab director this year, as our actual lab director and project co-director, Dr. Jill, could only be in the field for a short time this season.

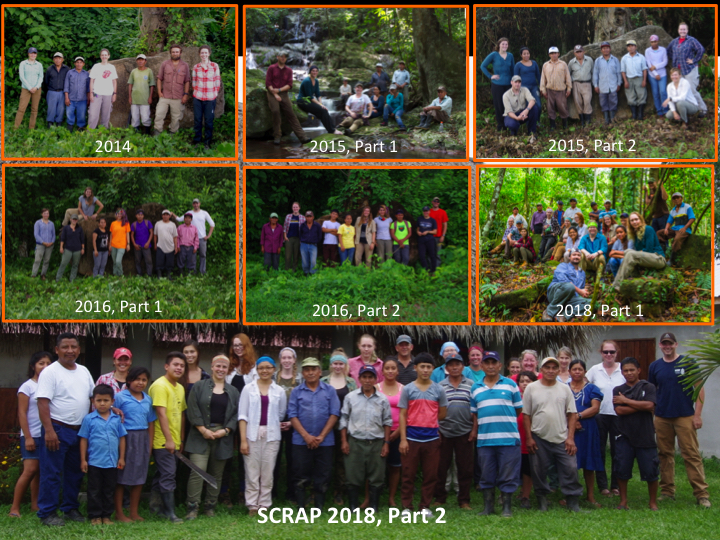

The details of my role have shifted over the years as our project has grown. Here are some of the additional tasks I took on each season in addition to those mentioned above and below:

• 2014-2015: I was on the ground with our small team surveying (walking, observing) along every orchard row of the Alabama property. Those were extra hot and tiring years! Mr. Juan Paquiul, who still works with us today, was also part of that work.

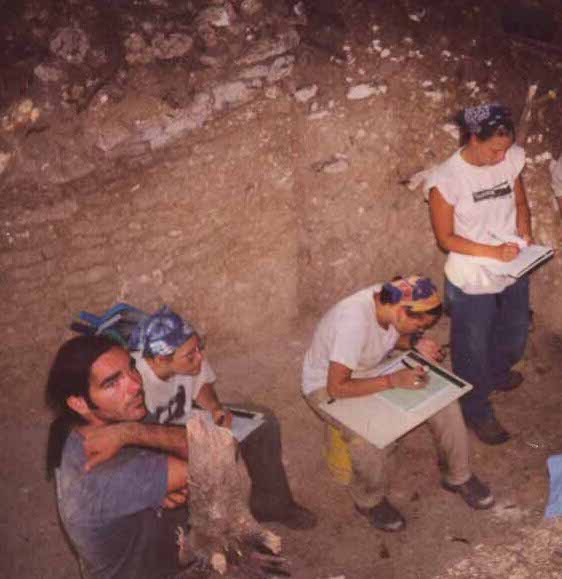

• 2016: This was our first year of excavations, uncovering small house mounds in the settlement, so I was training field supervisors and local field assistants on our excavation methods and recording while Dr. Shawn mapped the monumental core (“downtown”) of the Alabama site. Mr. Idelfonso Cal was with us that year and is still helping to train new field assistants.

• 2017: This year, we took a short break at the end of our one grant while we applied for the next. I spent much of the year writing about and presenting the results of our first three seasons. Also, I returned to Belize to do some outreach in schools and present at the annual, public-oriented Belize Archaeology Symposium.

• 2018: We hosted an undergraduate field school, so much of my time revolved around organizing, directing, and accommodating our group of students alongside our research team. Mr. Justino Chiac joined our team at this stage and, thankfully, has remained!

• 2019: I actually supervised my own excavations!

• 2022-2023: These last two years have primarily been filled with outreach and getting our artifact assemblages and type collections in good working order for future researchers.

• 2024: This coming year will be full of partnership and consultation meetings to plan future stages of research for SCRAP, as well as lots of writing!

I also must keep updated on local cultural, economic, and political developments, particularly as they pertain to SCRAP—this is challenging but necessary and requires me to talk with (“network”—blah! I hate that term!) many diverse peoples, communities, and organizations across the district and beyond. This is inherently challenging as I often suffer from significant social anxiety. But it helps that Belizeans are extremely welcoming people and are intrinsically interested in their pasts and not shy when providing insight and feedback; working with people in the Maya communities of the Stann Creek District is particularly rewarding.

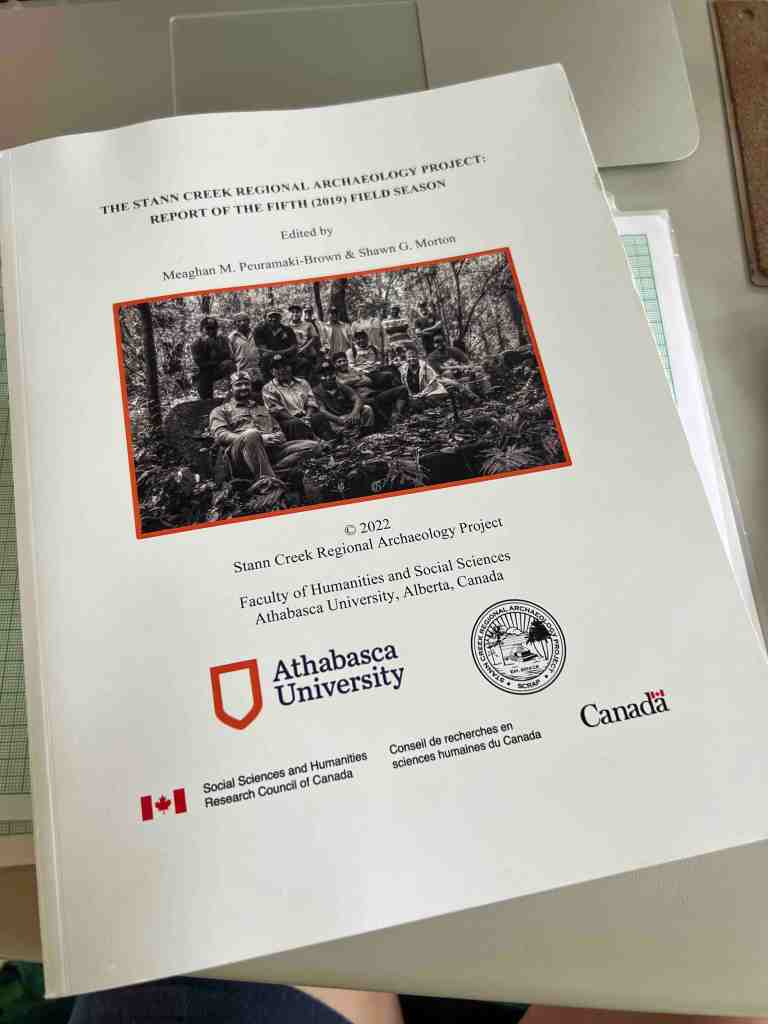

I’m responsible for coordinating the pulling together of our field results each season. These come in the form of a preliminary report, submitted to the IA before I leave the country, and include copies of ALL our documentation from excavations (e.g., notebooks, forms, artifact counts/catalogues, photographs, spatial data). Then, before we are granted our subsequent permit (these are given annually), we must submit our final report, which is a detailed write-up of our results, including layer-by-layer descriptions of our excavations. These reports are typically 100s of pages long. We present all final reports to the IA and post them on our project website. Using information from these reports, I coordinate academic and public presentations for our team members to give and help publish articles, news stories, etc., about our work. In fact, right now, we’re writing a book all about our project—if you see me, Dr. Shawn, or Dr. Jill, with our heads down in our computers, that’s likely what we’re up to as our manuscript is due to the publishers in August 2024!

Being the PI of a research team in Belize is a lot of work, but suggesting you do it alone is disingenuous. An essential part of being a PI is gathering a group of dedicated, intelligent, qualified, eager, and trustworthy individuals who can ultimately do the job with little required interference from you. You must also be willing and able to delegate to these other capable team members (not an easy task for many of us control freaks). Over the 7 field seasons of our project, we’ve gathered a fantastic group of Belizean, Canadian, and American researchers and assistants and an excellent network of supporters, advisers, and colleagues. I’m really proud of our small team.

Finally, being PI requires you to constantly think about the future and ask what it is we contribute to Belize and local communities—beyond just providing “knowledge”—and how we can continually improve. That is both the challenge and the reward!

Cheers from “The Field,”

Meaghan